45 CFR Part 75: Understanding the Strings Attached to Your Grant Award

45 CFR Part 75 – Overview of Grant Funding Regulations

Grant funding vehicles are used by the federal government to advance innovative research and development projects and are frequently thought of as “free money.” While the government oversight of a project funded by a grant is less intrusive than a true contractual relationship with the federal government, there are still rules that need to be adhered to — including audit oversight.

Specifically, there are two types of audits that all grants, cooperative agreements and similar assistance awards are subject to:

Uniform Guidance Audits as required by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Department of Energy (DOE). For this whitepaper we will use “UGA” to include any agency variations of this type of grant audit.

The annual Incurred Cost Submission. This “true up” report is the primary document used by government auditors to negotiate final grant costs, including indirect costs. The OMB offers a deep dive into all the requirements.

One of the key concepts of grantsmanship presumes that grantees act with integrity — to the point of policing themselves. While it is difficult to police yourself when you don’t understand the rules, it is your responsibility to understand them.

This whitepaper will explore UGA requirements, including dollar thresholds and due dates. Then we will address the most common UGA findings we see in our business.

Later, we’ll discuss a disturbing trend we’ve noticed. We’ve coined the term “Inadvertent Fraud” to describe the phenomena. As the competition for grant funding has intensified over the years, we’ve noticed an alarming number of grantees who bid indirect cost rates below their funding agency’s indirect rate audit thresholds (aka “safe rates”).

Backing into an indirect rate that mathematically falls below the agency’s safe rate allows the grantee to avoid a pre-award indirect rate audit. However, avoiding the scrutiny of the indirect rate audit seems to lead to complacency surrounding the proper accounting for grant funds as grantees feel like they must be “ok” – or someone from the government would have said something.

NIH & DOE GRANT AUDIT REQUIREMENTS

NIH and DOE Grants are Subject to Uniform Guidance Audits (UGA)

If an NIH or DOE awardee has expenditures from grants that exceeds $750,000, then it is subject to a UGA. Effective for company fiscal years beginning after October 1, 2024, the threshold has increased to $1,000,000.

The awardee is required to hire and pay for a CPA firm professionally qualified to conduct this type of audit, which encompasses both financial and compliance components.

Once the audit is complete, the awardee submits the audit report to the funding agency identifying any “findings”, which are violations of laws, regulations or the provisions of the grant.

The auditor’s report is reviewed by the Inspector General’s Office (IG) for quality control purposes and the CPA firm’s work papers may be audited by the IG.

Finally, the funding agency follows-up on the findings with the grantee to ensure they have been remedied. Failure to properly respond could result in the agency freezing existing funding.

We occasionally receive calls from grantees who are trying to avoid being subject to audit. Regardless of how much funding has been drawn from NIH’s Payment Management System (PMS) or DoE’s Automatic Standard Applications for Payment System (ASAP), you are required to be audited based on expenditures, in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). This includes your reimbursable, allowable costs according to the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR).

Whether you are audited or not, you are still required to follow the rules.

COMMON UNIFORM GUIDANCE AUDIT (UGA) FINDINGS

The objective of a UGA is to ensure the recipient of federal funds has not violated any laws, regulations, the provisions of the grant, or any of the 12 compliance requirements. It is important to note that any overdraws or overbillings that occur must be repatriated immediately, and funds can be clawed back. Listed are some of the more common findings:

Issues with Subcontractor Monitoring

Sub-recipients of federal funds are required to comply with the terms and conditions of the prime recipient’s award. Prime recipients that pass funds through to a sub-recipient have a fiduciary responsibility to make sure the subcontract agreement contains the proper legal language informing the sub-recipient of their obligations. The most common audit findings we see relate to:

- Not properly informing the sub-recipient of their responsibilities under the award

- Prime recipients not properly monitoring sub-recipient’s use of federal funds in compliance with laws, regulations, and the provisions of the grant award

- The prime recipient not having a documented sub-recipient monitoring policy

Issues with Consultant Documentation

A subcontractor has a clearly defined scope of work on a project. Relationships with consultants are generally less structured. In order for the government to be assured that real work has taken place and that you aren’t just writing a check to a colleague, consultant’s invoices are required to be very detailed and must include a clear description of what grant number they worked on, what they did, when they did it, and the hourly rate charged. Additionally, there must be a written consulting agreement.

Improper Allocation of Cost Sharing

Some government agencies require the grantee to share the cost of the research and development effort. This is referred to as cost sharing. Think of this as the grantee and the federal government proportionally sharing in each dollar of a project’s total funding. As an example, an award may be granted with a 30% cost share. That means the grantee and/or its sub-recipients must fund $0.30 for every $0.70 of government funding toward the $1.00 of total project funding. Certain types of funding vehicles have mandatory cost share provisions. As an example, ARPA-E awards typically come with a 5% – 50% cost share requirement embedded in their agreements.

A common audit finding is that grantees don’t properly calculate the amount of their cost share, or the cost share is not applied consistently.

Salaries in Excess of Agency Specific Caps

Most government funding agencies place a limit on the maximum compensation allowed to be

charged to their projects. In order to compete for the best talent, we find grantees unknowingly

pay employees in excess of the compensation limits and try to charge the government because

they are not aware of the caps on compensation, or don’t know how to properly handle the

excess compensation.

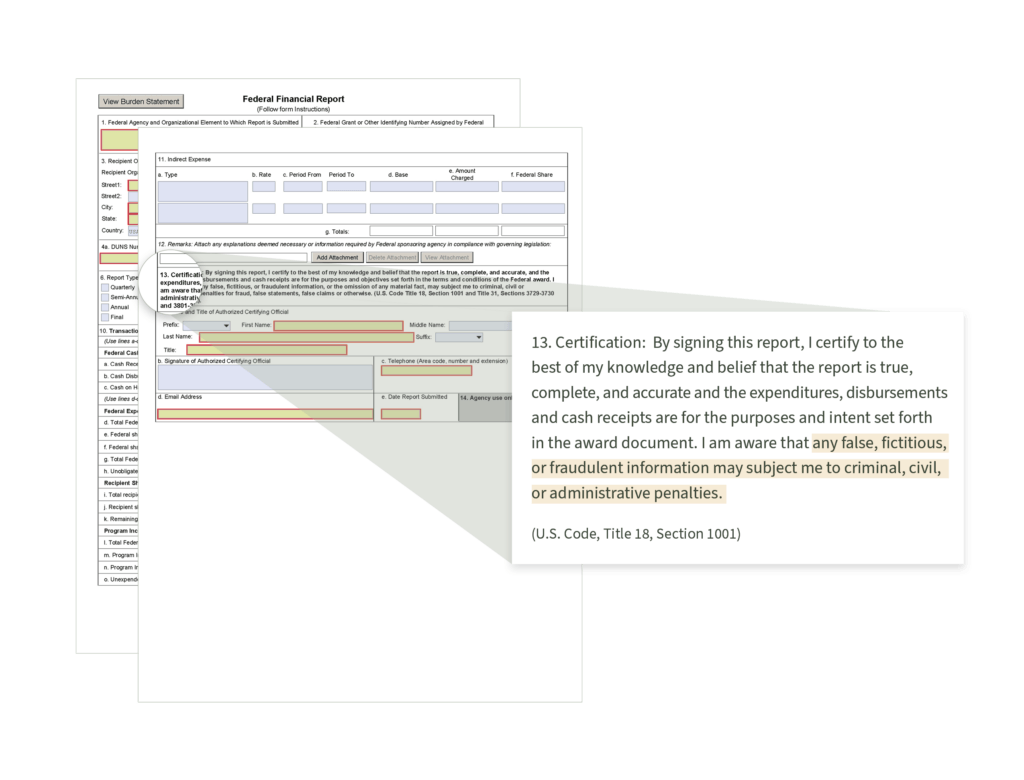

Improperly Filed Federal Financial Form (FFR)

The FFR is used to reconcile amounts earned in accordance with the NIH Grants Policy Statement to amounts drawn down from the Payment Management System.

The DoE required quarterly FFR filings. WIth NIH, the FFR is required on an annual basis (except for domestic awards under the Streamlined Noncompeting Award Process (SNAP)) and is due within 90 days of the end of your calendar quarter in which the budget period ends. A final FFR also needs to be submitted at the completion of the award agreement within 120 days after the end of the period of performance.

Please note: Similar language is embedded in every PMS drawdown in the fine print no one ever reads. Each time you click ‘Request Payment’, you certify accuracy.

Overdrawing Funds (overbilling the government)

As discussed above, NIH and DOE grantees are allowed to electronically draw funds from the agencies’ online payment systems. Billing the government, or “drawing down funds” is as simple as logging in, entering the amount requested, and presto – the funds arrive in your bank account the next business day. Funds should only be drawn down as disbursements are incurred and released to vendors. Drawdowns work on the honor system.

Overdrawing funds is one of the most severe findings, and funding agencies require the immediate repayment of funds. Overdrawing occurs in two common forms: overdrawing for direct costs and overdrawing for indirect costs.

OVERDRAWING FOR DIRECT COSTS.

Grantees are allowed to draw funds for direct costs incurred (actually spent and released to the vendor), yet we occasionally find grantees drawing funds for costs to be incurred in the future. We also see situations where the grantee draws lump sums of money, say $100,000, to bridge cash shortages even though their actual grant expenses incurred may be much less. This is usually a symptom of having an inadequate indirect cost rate which

we discuss in the Resources section found on our website.

OVERDRAWING FOR INDIRECT COSTS.

This finding is much more common! The government will reimburse grantees for indirect costs, or costs that are not directly related to a specific project, but rather, benefit all projects or the company as a whole. When a grant is proposed, the grantee includes an indirect cost rate in its proposal to cover such expenses. This “provisional”

indirect rate is typically a percentage of direct costs and is a temporary billing rate that must eventually be trued-up to actual expenses.

Sometimes an indirect cost rate will be negotiated prior to the award being funded. Other times, no negotiation is required, because the agency will approve very low indirect rates with “no questions asked”. For example, NIH SBIR grantees that propose an F&A rate of 40% or less do not have to negotiate their indirect rate – it is accepted as proposed. This can be known as a “safe rate”, but our observance leads us to believe that this can be anything but “safe”.

“INADVERTENT FRAUD”

Some grantees may commit “inadvertent fraud” as a result of not monitoring their actual indirect

cost rate, and not maintaining proper job cost reports on an ongoing basis. The FAR requires

indirect costs to ultimately be reported and reimbursed at the lower of actual costs, or the capped

provisional indirect rate.

Follow the potential trap:

- You receive a grant and think of it as “free money.”

- You requested a low provisional indirect cost rate (F&A rate < 40%) in your proposal, so you didn’t have to negotiate your indirect cost rate before your award is funded.

- Because you didn’t go through the indirect rate negotiation audit process, it’s not obvious that you are still required to calculate actual indirect rates and adjust your billings at the end of the year.

- You establish a billing relationship with the PMS or the ASAP systems whereby you push a button and whatever you requested shows up in your bank account the next day.

- When you file the FFR on a quarterly basis, you simply fill in whatever amounts you have drawn as being “earned”.

Expenditures must be based on generally accepted accounting procedures (GAAP) – including properly maintained job cost reports and indirect rate calculations. Grantees must also consider the FAR, Agency supplemental regulations, vehicle funding restrictions, and any cost sharing language or restrictions placed in each specific grant award.

“Inadvertent fraud” may be committed when signing the certification located on line 13 of the Federal Financial Form (SF 425) (see image above).

It is critical to understand that if you don’t negotiate your indirect cost rate, your indirect rate is capped at whatever you proposed. As such, you have forfeited the right to re-budget other spending categories to pay for indirect expenses that exceed this cap.

HOW TO MANAGE YOUR RISK

As experts in government award accounting, with over 40 years of experience, clients from coast-to-coast, and over $6 billion in awards managed, we know all the agencies, regulations, and how to help you avoid the pitfalls. We also know how to help you manage risk in accordance with your business goals.

We hope these insights help you better manage your grant funding award and avoid audit findings. We are happy to discuss your needs and concerns to see if we can help.

Ready to get started?

Contact a government funding award expert today.

833-415-3900

I’ve been in practice for over 40 years helping our small business clients procure, manage, and survive audits on more than $6 billion in federal government contract and grant funding. We’ve been featured presenters and panel moderators at Tech Connect’s National SBIR/STTR conferences since 2010, and I’ve presented at the DOD’s Mentor Protégé Summit and present regularly for several state and local organizations.

GET THE SOLUTION YOU NEED NOW

Learn more about how we can support your needs and objectives. Join us for an enlightening discussion and take the first step towards a partnership that can make a difference.

JOIN OUR NEXT WEBINAR

Join us for an upcoming webinar where we’ll dive deep into the latest insights and strategies.

Reserve your spot today and take a step toward gaining valuable knowledge that can make a real impact.